When Roger Ebert died, I realized that I was grateful to him for two things. First, he was the most interesting communicant on my Twitter feed and I always looked forward to his Tweets. He was generous with his film reviews and thoughts, and when he found interesting sites, he always shared the links.

Thinking I would miss them, I remembered an earlier gift from Mr. Ebert. The year his little book THE PERFECT LONDON WALK came out in England, I picked up a copy when I was in London for a few days to see my daughter, an archeology student. I was staying at Brown’s Hotel, where I was treating myself to a couple of nights before moving to my usual B&B at the side of the British Museum. As I recall, I decided to do the walk with the book held open in front of me. I had a day to do this; why not? I remember …

I wake up, eat an English breakfast, and take the Underground to the Belsize Park stop, studying the map on the way, then exit onto Haverstock Hill and start walking. “Cross the street and turn half-right down Hampstead Green,” I read. Half-right? O.K. I pass a pizza parlor that was once a bookstore where George Orwell had worked. I’m excited to be approaching Keats’s house, but to my disappointment, it’s closed. I can’t remember if I am there on the wrong day or at the wrong time. I can at least go up the walk to the gate and look through the window at the serene parlor; I can stop under the plum tree where Keats heard a bird singing and wrote “Ode to a Nightingale.”

I pass the ponds—my daughter swims in one when she is working on a dig nearby and living in a tent; on this trip she and her friends from the dig will drop in on me while I’m still at Brown’s Hotel and take advantage of the tub, shower, towels, and endless hot water.

Ebert’s book leads me to the summit of Parliament Hill, the highest place in London, where I can see the skyline of the city. I sit on a bench and enjoy the view. Of course there is someone flying a kite.

Then I strike off across The Heath, warned by the page in front of me that I might get lost, but the book tells me to look for a tree with a curious knob on its trunk; I look up and there it is. “It will be beside a little ditch, which you should hop across.” I keep going and soon I’m at my lunch stop, the Spaniards Inn. If I dined there, I don’t remember, but next I come to the Great House of Kenwood, which is open to the public. I have an appetite for Great Houses. I devour the smallest details—do the chairs look comfortable, what are the titles of the books on the shelves in the dim library we’re not allowed to enter, is that rock music coming from the second floor? I’m amazed to look through a huge window to see an ancient oak—a specimen tree, perfectly formed and perfectly framed—and yet it must have been a twig when it was planted. How did the architect—or the gardener—know that it would grow to be perfectly centered in that window? The most important thing in Kenwood House, by the way, is a late self-portrait by Rembrandt, and I’m a big fan of Rembrandt selfies.

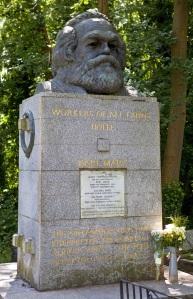

Onward—getting closer to my real object—I pass through the gates to Highgate Cemetery, walk straight along until the path forks, turn left, and in minutes I am looking up at the massive bust of Karl Marx. My first job—no, my second—when I arrived in New York City fresh from my state university was copyeditor-proofreader/ at The Weekly People, the broadsheet newspaper of the Socialist Labor Party, published since 1891, a paper I’d seen at the top of subway stairs being sold to commuters on their way to work. The editorial and business offices of the party along with the linotype machine and the printing press itself were in a cavernous warehouse at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. This was the tanning district, where I stepped over discarded hides on my way to work. In my spare time there, I read the archives—articles written on travels across the country to recruit and give speeches by the party’s intellectual, Daniel DeLeon, and accounts of actions by the party’s legal defender, Clarence Darrow. For a 21-year-old reader of John Dos Passos, it was heaven. I am probably the only person you know who once a year proofread the annual publication of The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte by Karl Marx.

There are always flowers on the grave.

Leaving Highgate Cemetery, I pass through Waterlow Park and its shaded paths and ponds, to hear, as is halfway promised in the book, a concert in the band shell. Certainly everything I have seen has been detailed in the book. Now, thank goodness, I read that it’s time for tea, and I find a teashop very near Fisher & Sperr bookshop, where I pay a short visit.

I’m given the option of walking down Highgate Hill to the tube to take the Northern Line back to my hotel, which will allow me to pass the spot where Dick Whittington, sometime before Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales, sat down and heard Bow Bells bidding him to return to London, where he will be three times elected mayor. The stone he sat on and a bronze statue of his cat mark the spot.

It was a perfect London walk.