When I see news stories of faked memoirs, I remember that I was once taken in by a memoir so persuasive and transporting that I would forgive the author anything. “Write another!” I would tell her.

I found a copy in a second-hand store when I was 14, but already bookish enough to note that it had been printed in 1929 and was a first edition, and to assume, from the endpapers and the name on the spine, that it was the story – the adventures – of a girl I would like to be. She grew up on a clipper ship in the South Pacific. Just the life for me! I would not learn for almost 50 years that the book was regarded as a great hoax – a book that was presented as autobiography, but was, in fact, pure fiction.

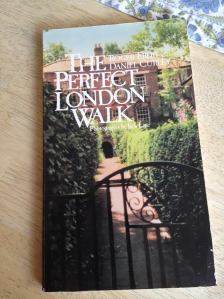

In the early weeks of 1929, Joan Lowell, 26 years old, was having the time of her life. Her publishers, Simon & Schuster, had told her that the first run of 75,000 copies of her debut book would be followed by another 75,000 before the month was out. It was receiving ecstatic reviews on both sides of the Atlantic, and best of all, the fledgling Book of the Month Club had announced its March choice: “Cradle of the Deep,” the story of a girl raised on the China seas by her sea-captain father. The public embraced the story and it was selling briskly – the Great Depression was just a cloud on the horizon.

Simon & Schuster gave a publishing party for Joan and 500 guests onboard the Isle de France in New York Harbor. Among those invited was director D.W. Griffith, who announced that he would film the story and star Lowell as herself – not a stretch, actually, because Joan had been an ingénue in Hollywood and landed a bit part in Charlie Chaplin’s “Gold Rush.” Perhaps her mentor Edward L. Bernays was among the guests. And surely her new – fairly new – husband, playwright Thompson Buchanan, was by her side. They had left Los Angeles together to come to New York City to become successful writers, to become stage actors—to become famous.

Birth records show that Joan was born in Berkeley, California, in 1902 and that her birth name was Lazzarevich. Later she would supply the 1936 edition of Who’s Who with the information that her father was Captain Nicholas Wagner and her mother was Emma Lowell Trask (she would act under the names Lowell and Trask). Candidates for Who’s Who traditionally supplied their own data, including DOB, and the publisher took the subjects’ information at face value. Joan’s birth name and date of birth are often missing in biographical data. Much of Joan’s information on Wikipedia is wrong, especially the account of her early childhood, which is taken straight from her book.

Joan attended Berkeley High School and the Munson School for Private Secretaries in San Francisco, but she must have been dissatisfied with her prospects because around 1923 or 1924 she went for a visit to Los Angeles, where she was soon cast as an unnamed saloon girl in Chaplin’s film.

She was in two more silent films, “Cold Nerve” and “Loving Lies.” She got third billing in the last, a melodrama about seafaring lives which was written by writer/actor Thompson Buchanan. After meeting on this project, they decided to go east together and seek their fortunes. While they were both acting in a traveling troupe, they secretly married.

In New York City, Joan tried her hand at acting, playwriting and journalism. She came under the wing of Bernays, known as the father of modern public relations. It was he who encouraged her to put her “yarns” into a book.

In “The Cradle of the Deep,” Joan, raised from infancy to 17 onboard her sea captain father’s clipper ship, comes of age in an unusual and exclusively male environment. She learns domestic skills from the sailmaker and the cook; she learns arithmetic by calculating her father’s course; she studies cultures when the ship puts in at exotic ports; and when she asks about sex, her father allows her to assist in the dissection of a pregnant shark. Joan was every girl’s heroine; feisty and adventurous, following the sailor’s code: Never squeal on anyone, take punishment without a squawk, and never show fear. My code as well. And although I lived totally landlocked, it seemed important to me, too, to learn to spit into the wind.

Lowell’s immediate success blew up in her face. The questions began, including whether a girl who had demonstrably lived most of her life in Berkeley, attended Berkeley High School and a San Francisco secretarial school could have racked up 100,000 nautical miles on the open seas. Most vociferous were sailing experts who questioned her savvy – gained, they claimed, “20,000 leagues away from the sea.”

There was a powerful backlash against the book, and it was said that members mailed it back by the thousands to the Book of the Month Club, which paid in full. It was not that readers hated the book, or hated the author. It was that they had loved the book extravagantly, and were heartbroken to learn that it was fiction.

In England, where the book was popular, readers laughed at what they called “an absorbing scuffle in Printer’s Alley.” They labeled it autobiographical narrative, perhaps another term for what recently is being called fictionalized memoir. “We on this side of the water are less concerned that our light reading should be veridical. All we ask is that it should be reasonably well written and amusing enough to carry us . . . so that we shall not mind a stretching of our credulity now and again,” said the Observer.

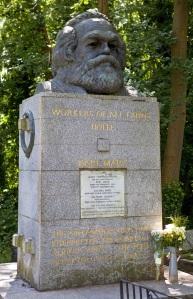

Lowell’s own response – the only relevant quote I could find – is the claim that “Truth is contained as much in the dreams and legends of people as in the factual chronicle of their lives.” The book continued to be categorized as nonfiction. In “80 Years of Bestsellers From the New York Times,” it is listed as No. 3 of the top 10 bestsellers of 1929, with the note “The sensational spit-in-the-wind ‘Cradle of the Deep’ followed in ‘Trader Horn’s’ footsteps.” That reference is to the book by Alfred Aloysius Horn recounting his youth as an ivory trader in Central Africa – supposedly a true story.

I knew nothing of this controversy, I hadn’t been born yet. My family in St. Clair County, Alabama, made an annual trip to Birmingham to visit the dentist and do Christmas shopping. I had very early discovered the city’s second-hand bookstore. There I found a battered copy of “Cradle” and it became my favorite book, for years my most revisited book. I was especially thrilled by the scene in which young Joan witnesses childbirth on a Pacific isle. I knew nothing about sex or childbirth. This girl was boldly pursuing the subjects that puzzled me.

Years later, when my children were young and we spent summers on Big Cranberry Isle in Maine, at the church bazaar and yard sales old copies of “Cradle of the Deep” would turn up for a quarter or even a dime. Copies were still plentiful, because between them the publisher and the book club had run off thousands. I bought copies for my girls and for their friends. These young readers loved the book as much as I had.

Twenty years later, when my oldest daughter decided to try her hand at turning the book into a screenplay, I had to pay a bookfinder $60 to locate a copy. To help expedite the screenplay, I volunteered to try to track the copyright renewals. A few lines on the Internet alerted me to the book’s history as a hoax, and my focus switched from the book to its author.

On a trip to California, I searched the Berkeley Archives and visited the Alameda County Courthouse and its museum room. The Academy library in Los Angeles came up with her film credits and a publicity still that showed her as a classic beauty, with the strong jaw, nose, and brow of beauties of that time – Irene Dunne, Joan Bennett.

I also searched magazine and newspaper archives. There was another disappointment in 1929, after her book was dragged through the mud. In September, Thompson Buchanan opened a play at Christopher Morley’s Hoboken Theatre with Joan in the lead role. The play closed two weeks later. A New York Times reporter tracked the author to his apartment at Washington Place and asked him directly about a report that the couple might file for divorce because of what their spokespeople had called a “recently discovered incompatibility of temperament.”

Buchanan told the reporter, “I did not know what temperament was until the failure of my play ‘The Star of Bengal,’ in which my wife was starred.”

Undaunted by these reversals, Joan sank what was left of her book money into writing and filming “Adventure Girl” (1934) in the West Indies and Central America, with the vague notion it would prove that although “Cradle of the Deep” was not true autobiography, it might as well have been. After all, she added, “Any damn fool can be accurate – and dull.”

In this “fact and fiction” talkie, Joan plays herself as she is buffeted by a hurricane, battles a boa constrictor and an octopus, and is nearly burned at the stake by hostile natives (“most of whom are smiling in amusement,” noted a review). By now, she was billing herself as a globetrotting explorer, skilled mariner and deep-sea diver … don’t laugh, the movie turned a profit for RKO. She was finally living the life she had imagined for herself.

That life continued to be one of high adventure. In 1935, on a cruise, she fell in love with the ship’s captain, who inspired her with his ambition to carve an empire out of the Brazilian jungle. He didn’t believe she could do it; to prove she could, she lived on a remote beach, where he was supposed to pick her up a year later. He didn’t show up. She tracked him to New York City, where he’d been offered the job of director of the Port of New York. Persuading him to follow their dream, she married her captain and they went to Brazil, with little capital but lots of energy.

They took on the job of building a 100-mile road into the jungle in the state of Goiaz. After three years of backbreaking labor, along with the workers they could find, they finished the road. The reward: Land. Thousands of acres.

Even her death in the Brazilian jungle in 1967 was dramatic and mysterious and unexplained. Her obituary in the New York Times declared that her book “created one of the most sensational literary controversies of its time.” I looked over my clips and notes and photocopies again after the James Frey affair had run in the press and on TV for longer than seemed justified. I picked up her book again. How important had it been to me as a young reader to believe that the book was true? At the time, I was convinced – the endpapers alone are convincing, with their map of Joan’s adventures, her portrait and the reference to her as Joan Lowell, the Captain’s daughter. I would not have wanted to be told that the story was not authentic. Nor would I have wanted my money back. I would keep the book. In spite of its history, it is one of those cherished books, read and reread and passed on.